The stereotype of a witch often includes broomsticks and pointy hats. We talked about broomsticks in a previous post which concluded the notion of flying might have emerged from overly superstitous imaginations. Can the same be said about the black pointed hat?

The topic was more complex than I expected.

Firstly, it’s hard to talk about the witches hat without talking about the history of pointed hats in general; the subject for a book more than a single blog post!

Secondly, there are already plenty of suggestions online as to the origin of the witches hat. These range from the tall hats of alewives to religious antipathy towards Quakers and Jews. While brewing could be seen as a form of magic i.e. the alchemy of mutation whereby elements change into something different, you could say the same about bakers and chefs. I didn’t find any connections to these.

The Jewish hat or Judenhat has been an accepted form of headgear going back to biblical times, but it became political in 1215 when the Fourth Council of the Lateran required Jews to wear a type of pointed hat as a visual distinction from non-Jews. This practice seems to have been extended to others accused of heretical acts such as sorcery, so the connection with witches is interesting but not proven.

Religious animosity towards the Quakers is also well recorded, as is their refusal to remove or doff their hats in front of anyone considered to be socially superior. While images of some Quaker women exist wearing tall black hats, many others seem to have worn flat bonnets or caps.

The church had narrow views when it came to alleged heresy so anyone not following official scripture was discriminated against. Quaker beliefs in equality, particularly between the genders which allowed women to preach, made them a prime target for accusations. One identified this way it was popular practice, especially among largely illiterate communities, to colour every one the same.

Another unproven theory is that the pointed hat resembed the horns of the devil. If this were so – wouldn’t it have double points like the fashionable hennin style hat worn by women of the aristocracy in the 15th century?

Start to explore this fascinating area and it becomes clear that pointed headwear has been around since the earliest civilisations. Ancient Mesopotamians and Sumerians pictured their gods wearing pointed hats, while the Egyptian pharoahs wore tall headgear representing the red and white crowns of upper and lower Egypt.

Mummified Tarim bodies have been discovered in central Asia wearing tall hats while the Phrygian cap, worn by both men and women throughout early middle eastern history and beyond is another contender.

I admit to being intrigued by the conical gold hats dated back to Bronze Age Europe, but rather than see them as connected to 17th century witches, these beautifully engraved artefacts should remind us there’s so much we simply don’t know.

Because of this, it’s easy to slip off track and get lost in the possibilities and maybes.

For example, I also came across theories suggesting the pointed hats represent the pineal gland, or third eye, and wearing one makes yourself nearer to whatever god your culture recognises.

Phew – is any of this true?

I don’t think so…

The reason can be found in published materials relating to witchcraft accusations where women are rarely seen in a black pointy hat.

Phamplets and chapbooks are a useful source. Take a look at some of these.

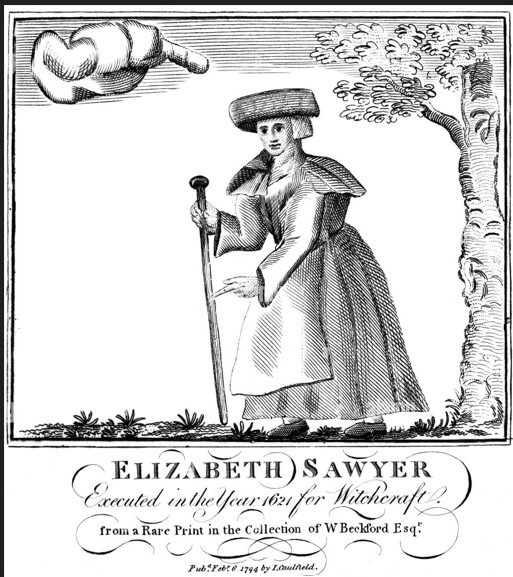

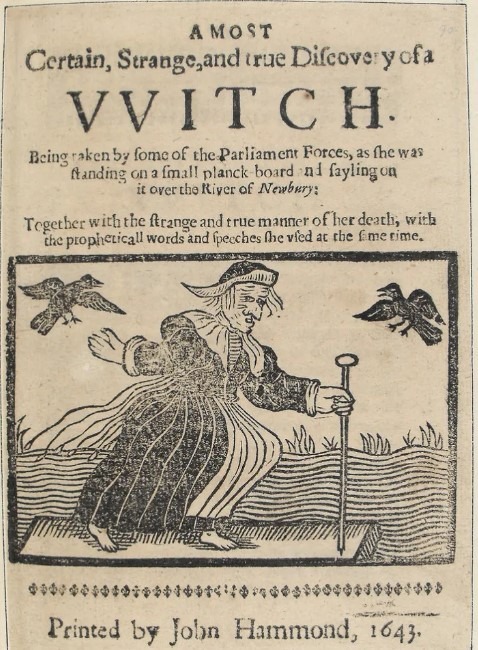

Elizabeth Sawyer (above) and the Witch of Newbury (below) are both wearing everyday caps without points.

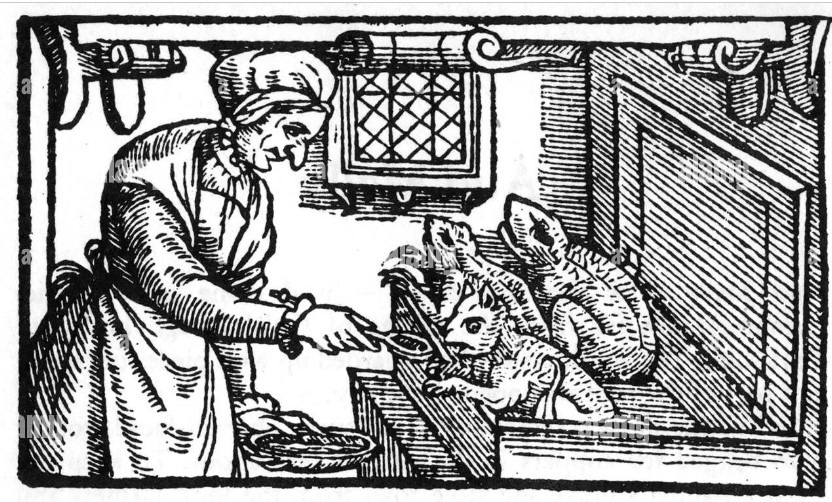

The lady in the 17th century woodcut below is wearing a cloth cap typical of rural communities at the time.

The frontispeice Matthew Hopkins (Witchfinder General) book, The Discovery of Witches, shows two alleged witches with their familiars but neither of them have pointed hats. Of the three people on this engraving it’s Hopkins who is wearing the closest version!

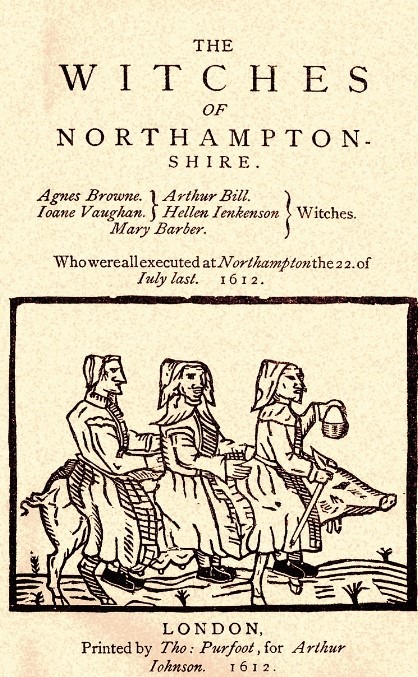

Another image below includes the idea of women travelling on animals, often thought to be a demon in disguise. Because this buys into one of the common witchcraft tropes, you might expect them to also be wearing pointy hats but no – their caps are plain fabric and flat.

There are many image online relating to the Salem witch trials in the US. Women are shown wearing cloth caps and bonnets whereas it’s the men, as in the image below of George Burroughs, one of the few men accused of witchcraft during this time, who are wearing black hats with conical tops.

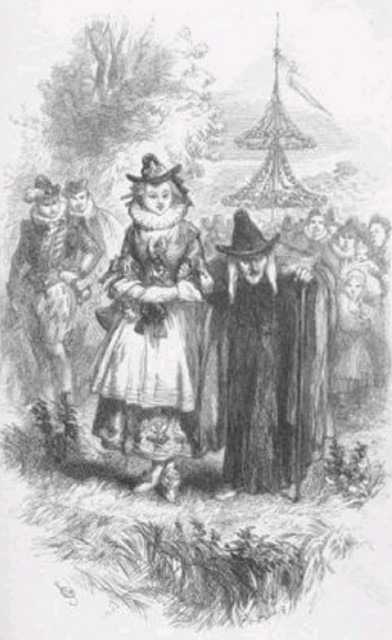

The image below does show alleged witches with the traditional head gear but look at the date. It’s 1854 – nearly 250 years from the case of the Pendle or Lancashire witches, the book is about.

John Gilbert-1854-in William Harrison Ainsworths The-Lancashire Witches Likewise, the image at the top of this post is from book published in 1896, and while there are wood cuts showing pointy hats, there are also those, as in the iimage below, without.

I wonder if the pointed hat is more fantasy. Maybe the hat is no more real than flying on broomsticks or suckling familiars. Maybe it’s part of the image – a socially and culturally constructed artefact or caricature – where very little, if anything at all, is real.