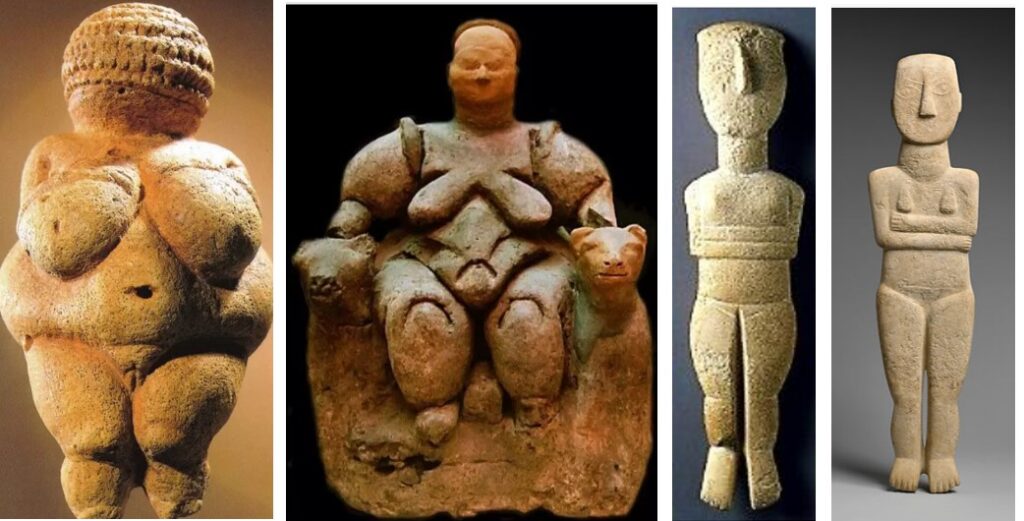

The differences between statuettes of larger size women, talked about in a previous post Lets talk ancient female statuettes, and those known as plank women from the Clyclades, are intriguing. Dated from the late neolithic to the early bronze age period (@5,000-2,000 BC), they’ve have been found in a range of styles but their function remains a mystery.

So many objects – so little information…

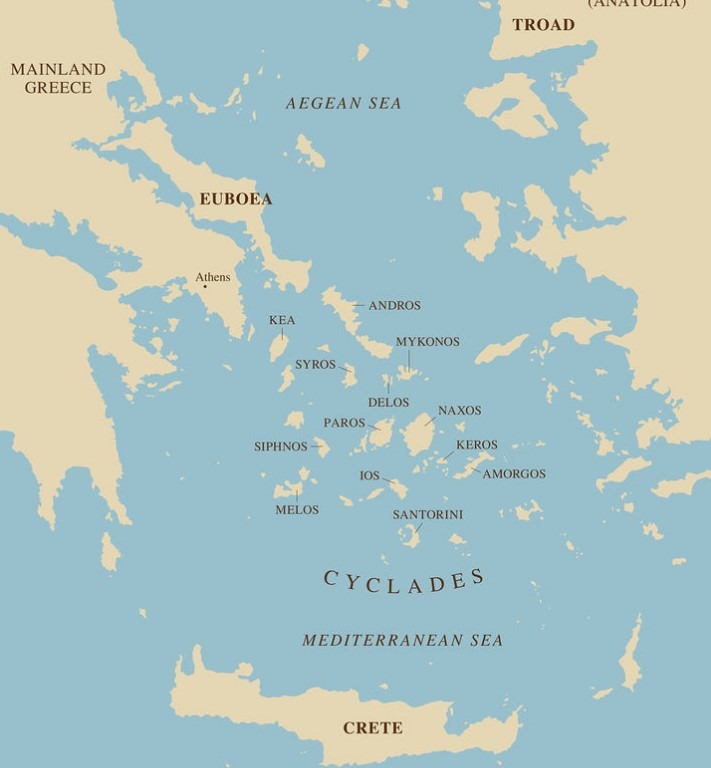

Willendorf Venus and the Seated woman of Çatalhöyük emphasise plus-size bodies while the plank women are predominantly thin and flat. Produced in a set of islands in the Agean Sea, between southern Greece and Turkey, these strips of marble are unmistakably female with a unique minimalism.

I first came across them at The Museum of Cycladic Art in Athens. I couldn’t have pointed to the Cyclades on a map, and had never heard of plank women, but I’d seen posters advertising the Star Gazer statuette which looked intriguing. It turned out the museum was a highlight of my week.

Ironically, Star Gazer was found at Kilia on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey. She doesn’t come from the Cyclades, is older than the plank women and not unique. The name Kilia figures or idols describes them collectively, alongside the epithet Stargazer because their heads are said to be tilting as if looking at the sky.

Having got into the museum, I discovered the world of cycladic art – or icons – fertility goddesses – talismans or funereal customs… From an archeological viewpoint, we know very little about these enigmatic pieces. Many have been exposed through grave robbing which supported the thriving black market for antiquities in the 20th century. They’ve also been the subject of fakes and forgeries. Inadequate documentation regarding their discoveries means a lack of contextual evidence about any authentic origins.

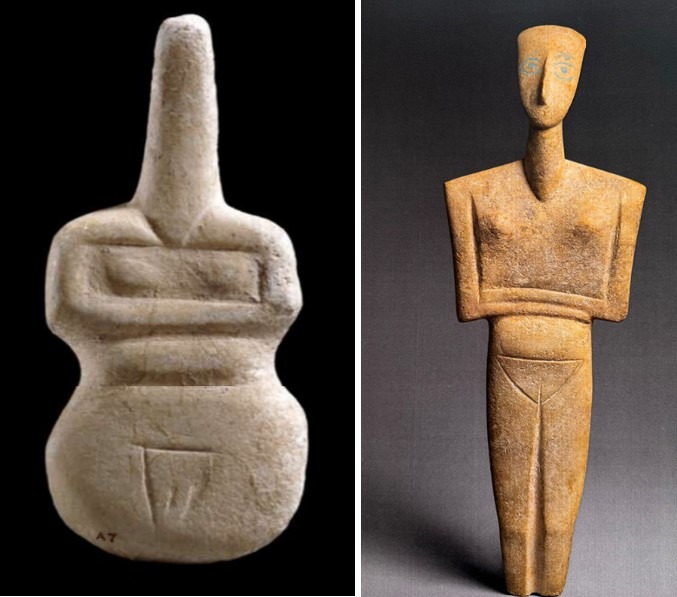

Development appears to have begun with the violin shaped figurines below, which I’ve always thought more resembled cellos! From the Cyclades, and dated to the late neolithic period (5300-3200 BC), they emphasise the neck, waistline and vulva area, while limbs seem to be irrelevant for whatever purpose they represented.

The carvings in the images below include heads. Again, they are from the Cyclades and dated to the late neolithic. One is carved while one appears to have been deliberately left smooth.

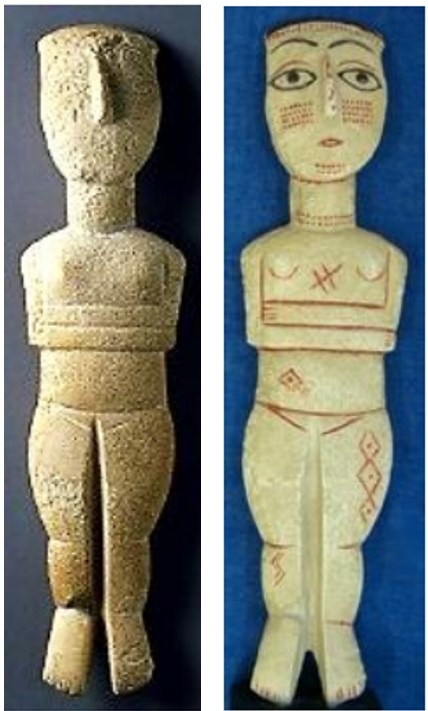

The cycladic periods, dated 3200-2800 BC, followed the late neolithic. From this time, physical details such as breasts and prominent noses begin to appear. There’s also the development of legs, and arms folded across the body. Some women, such as the one below on the right, have been found with painted features.

These lead chronologically to the typical plank woman. It seems different islands produced their own unique designs, but they all share a similar flat physique.

While the majority of found statuettes are women, some have what’s been interpreted as male genitalia, albeit with breasts, such as the image below on the left. Another ‘male’ figure has been called The Hunter because of the belt worn over the shoulder, thought to be used to hold a knife or other weapon. It’s worth reminding ourselves at this point that these are conjectures rather than proven facts. Truths about ancient history may never be known.

It’s also worth including examples of other figures from the islands which have been labelled as ‘male’ – the Harp Player and the Cup Bearer – both in the Museum of Cycladic Art. With ambiguous genitalia, it seems they’ve been designated as male because they portray ‘activity‘ whereas female representations are passive. This will be an interesting point to explore further in a future post.

So what was their purpose?

Here’s some suggestions I’ve come across…

- where archeological excavations have unearthed plank women, they were often broken and found in graves, leading to suggestions they were connected to funeral rites

- examples of art, with no purpose other than aesthetic

- examples of a middle eastern mother goddess religion linked to ancient fertility worship

- magical devices for practitioners of magic

- toys

- talismans

We simply don’t know.

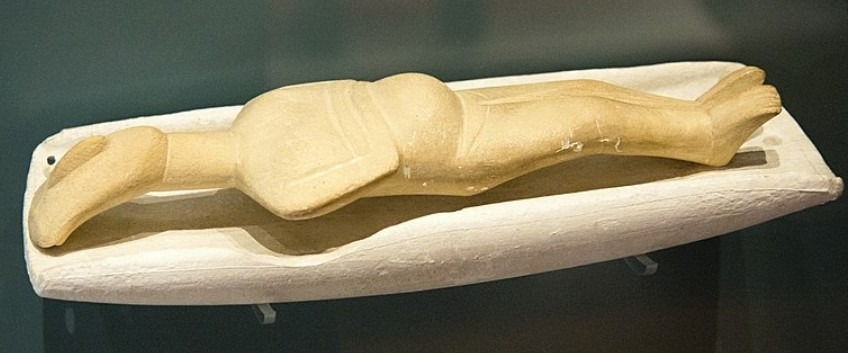

Few appear to be freestanding. Even those with clearly defined feet have been constructed in ways suggesting they were designed to be laid down.

While the majority are hand size, some are much larger. I saw the one below in the museum. The photo is a little blurred so details are unclear but she has clearly defined fingers. Like many others, by elongating the neck, her nose and breasts form an isosceles triangle. This – in a time before the recognition of mathematics by the ancient sumerians and developed further by the greeks – may have a significance we don’t yet understand.

The only common themes of the majority are they represent females and are made from marble. We know marble was widely available in the Cyclades and one reason suggested for this choice might have been its transluscent qualities, as shown in the image below.

They’re also strangely attractive and several 20th century artists were inspired by their simplicity. The tall thin sculptures by Alberto Giacometti and stone carvings by Amadeo Mogliadani, in particular his standing nudes, are said to have been made under their influence.

Earliest portrayals of the female body, as explored in Lets talk ancient female statuettes, appear to focus on fertility. This assumption is based on how these squat figures emphasised breasts, bellies and hips. Many thousands of years later, across an archipelago of islands in the Agean Sea, the Cycladic people seem to have largely ignored these features, with a few exceptions.

I wonder if these exceptions offer us a clue…

One statuette, reclining on a bed or pallet, was found on the Naxos. She appears to be pregnant, in contrast to the majority with flat stomachs. Another exception is what appears to be a family. We’ve already seen how different islands in the Cyclades appear to have produced different designs and the one below is attributed to the Keros and Syros cultures.

Despite the lack of defined genitalia the image could be described as a family unit with two adults holding a child. Maybe the lack of features is a deliberate choice, and they were designed to represent humanity without specific cultural constructions.

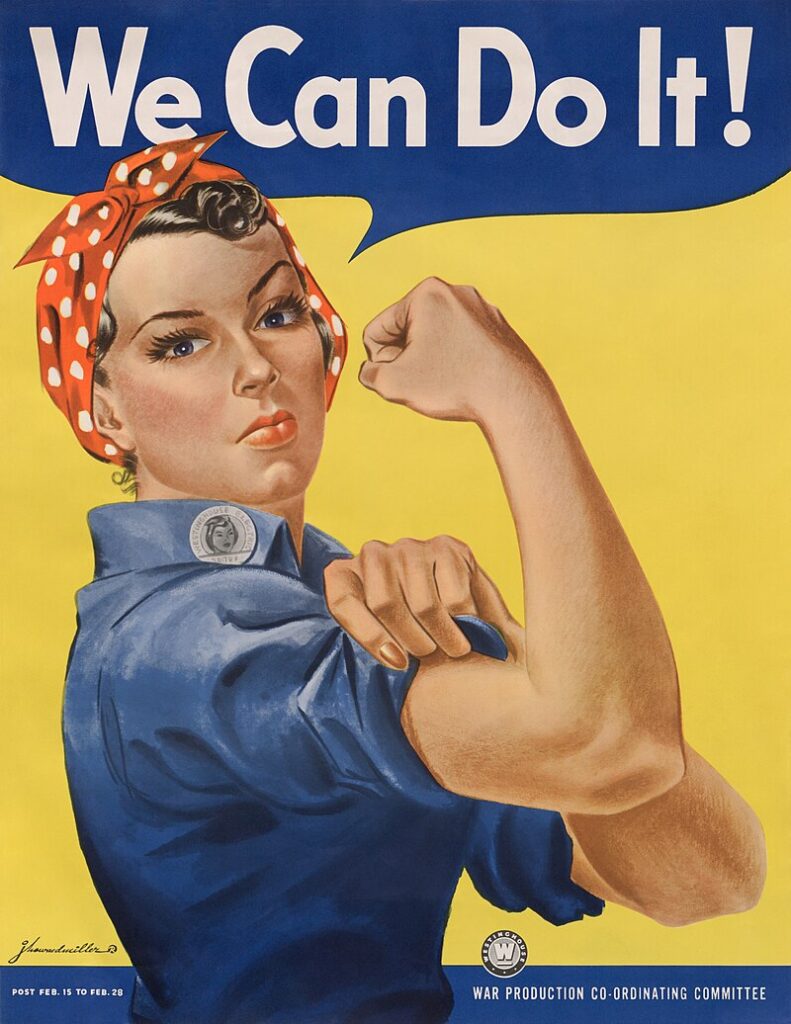

Researching this post, and reflecting on the largely featureless appearance of these women, I was reminded of the The Second Sex, published 1949, where Simone de Beauvoir wrote “one is not born a woman, but becomes one“. What counts as female comes through the processes of social conditioning in a patriarchal society.

When I began to write this post, I had no idea it would end up here!

The 1970’s saw the birth of French Feminism and écriture féminine (female writing). In an attempt to move beyond the phallocentric, writers such as Julia Kristeva and Luce Irigaray suggested alternative ways to conceptualise gender. As it is, we’re unable to ‘know’ gender outside of language. Girls born into a male dominated world have a lack of space for understanding what it means to be female, outside and beyond what patriarchy has constructed.

The Willendorf Venus and Seated woman of Çatalhöyük, from the previous post Lets talk ancient female statuettes, force us into an association with female size and fertility.

The cycladic women leave space for speculation.

Once biological essentialism has been removed, we’re free to rethink sex and gender along different lines. The clean minimalism of the cycladic plank women – with their endless possiblities for alternative constructions – may offer a valuable opportunity to do just this.