Selkies are shapeshifters. Unlike the half-woman half-fish mermaid, selkies make a complete transformation between human and seal.

Tales about selkies come predominantly from the far north; mostly Scandinavia, northern Britain, Iceland and the Faroe Islands.

The most common story goes like this…

Selkies like to come ashore, and shed their seal skin to sing and dance. A man, attracted to her beauty, hides her pelt, preventing her from changing back into a seal. After marrying, they have children but she longs to return to the water. One day she finds where he’s hidden her skin, slips back inside and leaves, abandoning her family, never to be seen again.

There are variations on the theme, but happy endings are rare.

So where do these tales come from?

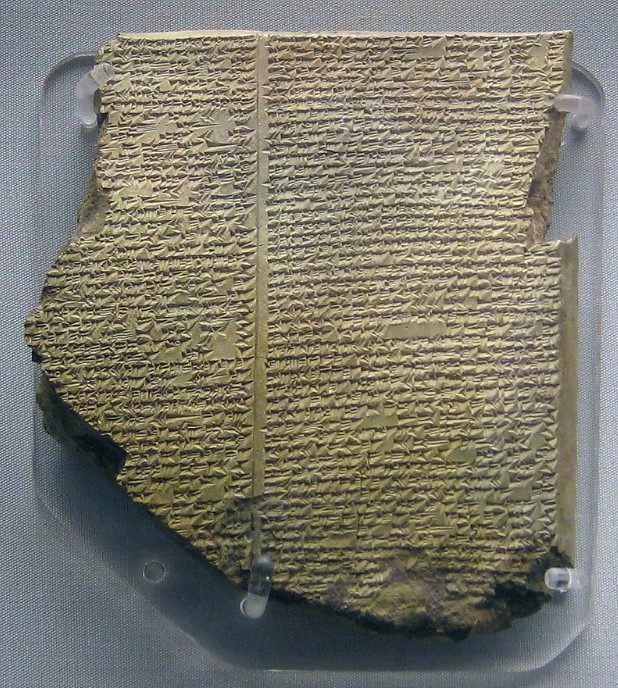

Shapeshifting is a common feature in myth and legend. One of the earliest stories is the Epic of Gilgamesh from Mesopotamia. The demon Humbaba gets involved in a fight with Gilgamesh and Enkidu. We know he can alter his appearance, because Gilgamesh tells Enkidu that Humbaba’s face keeps changing.

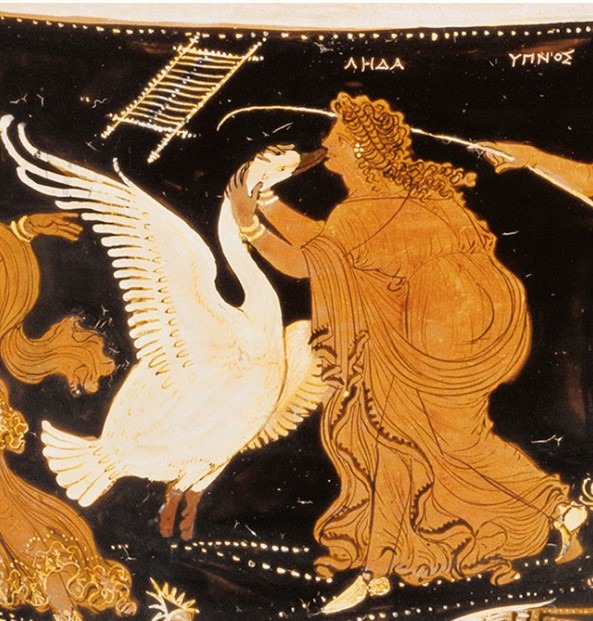

Greek mythology is full of shapeshifting, mostly by gods and goddesses, in particular Zeus who regularly took on different identities for seduction. He became a range of animals from ants (with Eurymedousa, mother to Myrmidon) and birds (he seduced his wife Hera as a cuckoo), to bulls (with Europa, mother of King Minos of Crete) and swans (with Leda, mother to Helen of Troy).

Zeus thought nothing of impersonating Persephone’s husband Hades, and even turned himself into a shower of gold to seduce Danaë, who consequently gave birth to the hero Perseus.

Ancient myths involving shapeshifting are common but seals are cold water creatures, which explains their absence from early civilisations based around the Mediterranean. Other parts of the world have stories about swan maidens, who shed their feathers to become beautiful women. Any man who steals their feathers can prevent them returning to their swam form. This trope suggests the principles of transformation may have been adapted for local environments.

Trying to get to the roots of the selkie, I found lots of online texts saying they appear in the sagas, for example Egils Saga and The Orkneyinga Saga from Iceland, and Hrólfs Saga from Denmark. But when I looked, I couldn’t find any direct references within the texts. If you can help with early sources, please let me know in the comments below.

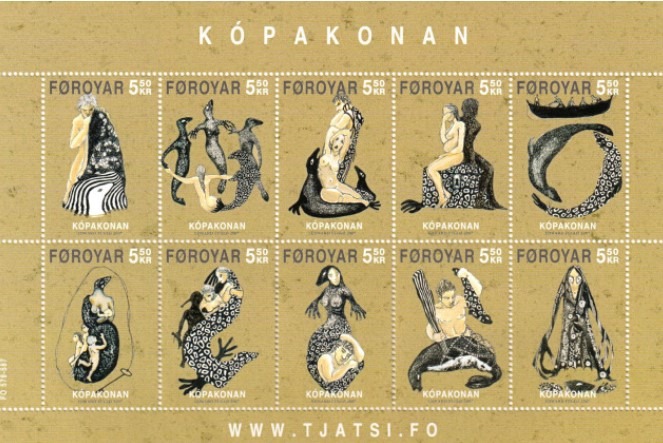

The word selkie comes from old names for seal, including selk, selch or selich. They are creatures of folklore known through oral stories and songs, in particular from Celtic and Norse societies. This cultural mix can be found in stories from the Faroe Islands, which were first inhabited by Irish monks in the 6th century, followed by the Vikings from the 9th century onwards.

The Legend of Kópakonan (Seal Wife) is captured in a statue by the harbour in Mikladalur on Kalsoy.

In this version, the fisherman hides the selkie’s pelt in a locked chest. He keeps the key with him at all times but the day he forgets, his wife finds her pelt and returns to the sea, where she is reunited with her bull seal partner.

Some time later, the men of Mikladalu plan a seal hunt. The fisherman dreams his selkie wife tells him not to kill the bull seal or the cubs because they’re her family. All the seals were murdered and the man takes the bull seal and cub’s flippers home. When he’s cooked the head and flippers, the selkie appeared as a troll who prophesises the fishermen of Mikladalu would die, by one means or another. All future deaths, whether by drowning or falling from the cliffs, were then blamed on the selkie’s revenge.

Iccelandic folklore tells a similar story – up to a point. In this case, after the woman found her pelt and returned to the sea, the grieving fisherman often saw a seal following his boat, and on those days he had a good catch. When their children walked by the water, a seal would appear to throw fish and pretty shells towards them, but the fisherman never saw his wife in human form again.

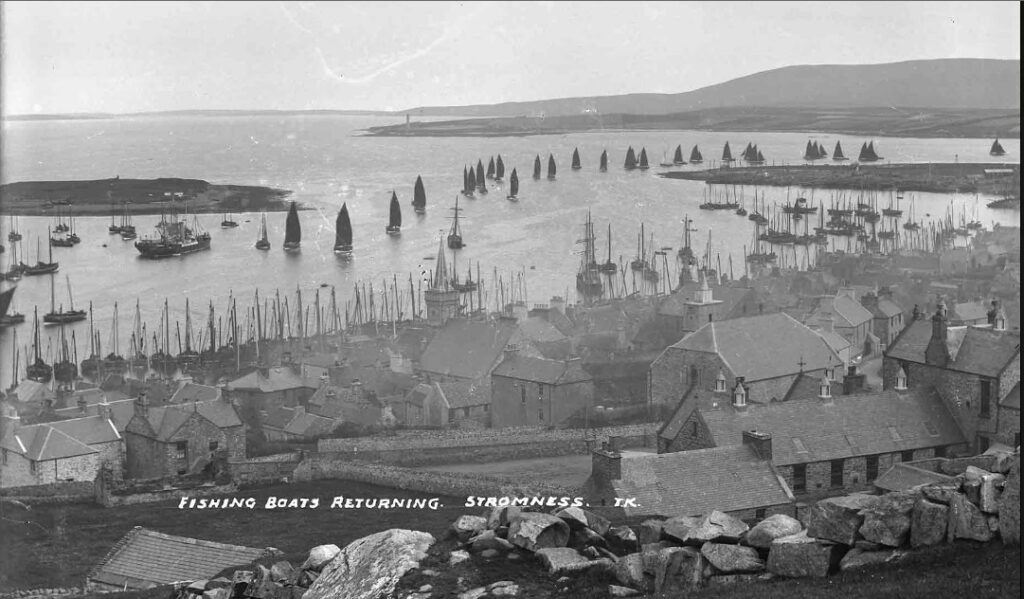

The Shetland Islands and Orkney Islands are home to many tales about selkies, both male and female. Collections include Tales of the Seal People: Scottish Folktales collated by Duncan Williamson and Orkney Folklore and Sea Legends by Walter Traill Dennison. Variations include recognition of an object like a knife or gold chain confirming a shapeshift had taken place, such as the story from Shetland called The Goita Skerry.

A modern interpretation can be found in Women Who Run With the Wolves; Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype by Clarissa Pinkola Estés who has reimagined the selkie in Sealskin Soulskin, where humans began life as seals.

However, the selkie doesnt seem to have captured artist’s and sculpter’s imagination in the way of the sheela na gig and mermaids. Maybe this is because the stories were limited to northern Europe, at least until folklorists such as Duncan Williamson and Walter Traill Dennison began to collect them and give selkies a wider audience.

In 2014, the animated film Song of the Sea was released by Cartoon Saloon. I love animations, in particular the work of Hayao Miyazaki, and although differently drawn, the universal messages of love and loss in the Song of the Sea still makes me cry!

There are folk stories where selkies can control the weather or possess other magical powers. Some are benevolent while others more malicious, damaging nets and stealing fish, and it’s been suggested these may show traces of older stories from the Saami people of Norway.

Around the 9th century, Orkney came under the political control of Norway who named it as Orkneyjar (Seal Islands). The old norse for seal was orkn while the Saami people were finna, hence the Finn folk.

The Saami hung on their pagan roots when other countries became christianised, so beliefs in shamanism and magic continued to influence the development of folklore in the areas where they lived. Orkney and Shetland have faires called trows from the Norwegian troll and trows had beautiful singing voices, as did the selkies.

Saami were known for their sorcery, including the ability to shapeshift into a sea animal. They could travel great distances by magic and, more practically, used sealskin for boats and clothes.

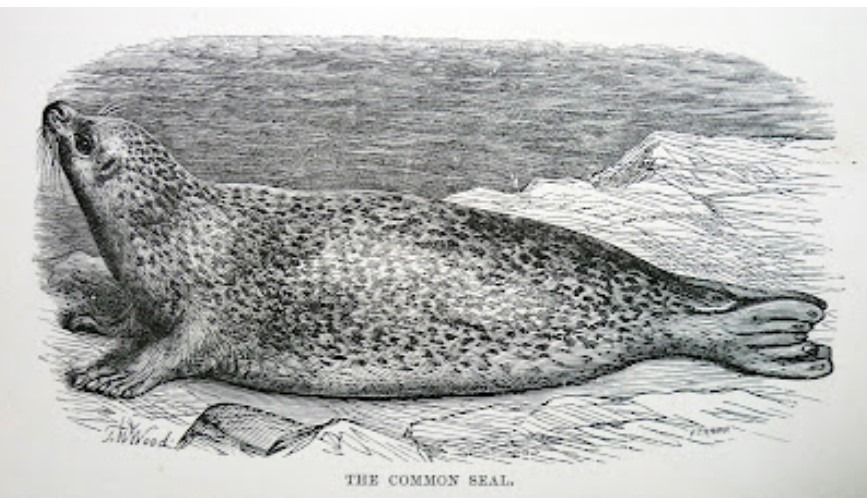

For as long as humans have existed, they’ve looked for explanations. This need for answers underpins the development of fertility myths and rituals, the rationale for accidents and misfortune, luck, love, and loss or simply poor weather. The selkie may well be an attempt to explain the unexplainable. Also, we love stories and seals are beautiful creatures. They are curious and seem to have a natural affinity with people, as shown in the video below.

Watching this, it’s not hard to understand why and how stories about selkies have developed and come down to us through all the years.