They have the power to stop you in your tracks.

It’s not a sight you see every day.

No one can be sure if they represent sex, sin, childbirth, or protection from evil but many are found on churches – which can feel a little discordant considering how the church had a real downer on women over the centuries.

Despite multiple theories and beliefs, the origin and purpose of sheela na gigs remains unknown. They are a mystery and I love mysteries like these.

The Oxford English Dictionary says the name is derived from the Irish, Síle na gcíoch, meaning “Julia of the breasts”.

Sheelas are known for different anatomy and rarely have breasts.

Leading researchers agree the name is more modern than ancient but that’s about all they agree on.

The first research is considered to be The Witch on the Wall: Medieval Erotic Sculpture In The British Isles by Danish writer and poet Jorgen Andersen, published in 1977. Prior to this, little secular attention had been applied to the carvings. Anderson attempted to group the different designs and locations, offering early theories around origin and purpose.

A decade later, The Witch on the Wall was followed by Images of Lust, Sexual Carvings on Medieval Churches by James Jerman and Anthony Weir. The latter has a wonderful collection of photographs from his research at beyond the pale. The authors concluded sheela na gigs were iconographic and, as in the majority of medieval church carvings, designed purely to convey the moral teachings of christianity.

Women in the bible tended to get a raw deal. Eve persuaded Adam to eat the forbidden fruit of the tree of knowledge; an act which led directly to their banishment from Eden and suffering for their offspring. Women would have pain in childbirth, babies born tainted with original sin, while men would eat food grown through the sweat of their brow until they returned to the ground: ‘for dust you are and to dust you will return’ (Genesis 3:19). Never mind original sin, this was the original punishment.

Michelangelo”s Fall of Man and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden in the Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo”s Fall of Man and Expulsion from the Garden of Eden in the Sistine Chapel

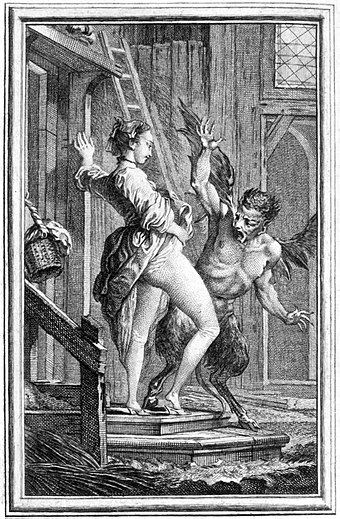

You only have to look at the 17th century witch trials to see how women were literally demonised by the church.

To compensate, they were expected to be obedient, chaste and above all silent, having to submit to their husbands as well as obey without question the word of god. Those who failed were punished and vilified.

The wife of Lot was turned to a pillar of salt for disobeying the almighty’s order not to look back as she fled her home town of Sodom. Delilah tempted Samson and cut off his hair, causing him to be captured, blinded, and set to work dragging stone. Jezebel – a name applied to women to this day – was thrown from a window and eaten by dogs for her wrong doings. The list goes on.

Women and the church did not have healthy relationships but at this point it’s worth remembering that medieval England was a pretty bawdy place. Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales shows sex was nothing to be shy about. Chaucer was writing in the late 1300’s, the time of the great medieval cathedral building and sheela na gigs are not the only example of what were later called lewd and obscene images.

Male genitalia was also on show in the churches and cathedrals of this time. Is it possible the carvings were examples of stone mason humour? I quite like that idea. But then we come to more feminist approaches to the origins of the sheela na gig, and the story changes.

in 2004, Barbara Freitag wrote Sheela-na-gigs, unravelling an enigma. The book re-examines connections with medieval buildings and religion, but its conclusion disconnects the carvings from the church and suggests they are older fertility symbols. For Freitag, their origins lay in folklore and were most likely related to assistance in childbirth.

Freitag was not the first to associate the female image with female culture. In the 1980’s two seminal works were published; The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of Western Civilization by Maria Gimbutas and The Great Cosmic Mother by Monica Sjöö and Barbara Mor.

Both collected huge amounts of data on statuettes, rock carvings, cave paintings etc, to support the thesis they evidenced ancient matriarchal goddess religions; a hypothesis which has remained popular.

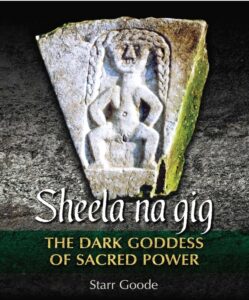

In 2016, Starr Goode wrote

These ideas have most recently been revised in

So where did the sheela na gig originate and what does she represent? The continuation of a pre christian goddess fertility belief or the result of the lusty stonemason’s imagination.

It has to be said that while sheelas are most commonly found on European medieval churches, some have been discovered elsewhere.

The sheela at Haddon Hall in Derbyshire was found in in what was originally the old stables and the hall dates back to the 11th century. Irish sheelas have been found in the walls of castles and buildings like the Round Tower at Rattoo, in County Kerry and one was carved into a wall in Fethard, County Tipperary. So they are not only found in churches…

The tradition of women exposing their genitals goes back to ancient times. Anasyrma stood for ‘lifting skirts’. The most famous example is in the Greek myth of Baubo. Demeter, in despair at the loss of Persephone, visited Baubo during her search for her daughter. Refusing the hospitality because of her grief, Baubo exposed her genitals in an attempt to make the goddess laugh.

Again, there is no fixed consensus on the original meaning of Anasyrma but, as well as a joke, interpretations include scaring away supernatural enemies, or a sign of mockery, like the custom of baring the buttocks in Viking and Scottish war traditions.

This is known as an apotropaic magic or ritual, meaning to avert evil and protect the individual.

Even the Willendorf Venus, now thought to be over 30,000 years old and still as much as a mystery as the sheela na gig, shows off a pronounced vaginal cleft.

It’s a bit like having your own personal talisman!

Whatever the explanation for their presence, sheela na gigs clearly represent connections between women and sex, be it lust, desire, sin or childbirth.

Some people mention the inclusion of ribs and say this is symbolic of the crone aspect of the triple goddess but maybe ribs are symbolic of Eve and refer to original sin? That’s a possible and maybe plausible suggestion I haven’t seen anywhere. It’s one which reinforces how, in the absence of evidence, these images represent the gaps where imagination can freely roam, and this is where their power truely lies.

2 thoughts on “Let’s talk about sheela na gigs”