Swarming is instinctive. Survival is hard wired into the honeybee’s genetics. If the time is right they’ll swarm and there’s little a beekeeper can do to prevent it.

Looking for signs a colony might be thinking of absconding is one of the reasons for weekly inspections during the season. There are clues to be found if you look for them.

The most visible clue is finding queen cells. These are elongated and hang down from the sides or bottom of the frame.

Queen cells are a sign the colony feels it is running out of space and they’ve converted one or more eggs into potential queens. When they swarm, the old queen will leave the colony, with about half the total number of bees. The remaining ones will rear a new one.

The queen cell is capped on the 8th day so inspecting every 7 days gives the beekeeper opportunities for intervention. The books say a capped queen cell shows the colony has already swarmed but many times I’ve found them before they’ve absconded. Bees do their own thing!

You can try to buy time by taking out the queen cells but spotting them all can be a challenge. The bees are experts at hiding them. You can also split the colony by creating a nucleus hive with either the old queen, if you can find her, or the frame with queen cells plus lots of bees.

Whatever method you prefer, once the colony is in swarm mode it can be hard to stop. Last month I had swarms on two consecutive days. It was a busy weekend.

Bees swarm in two stages. About half the colony leaves with the old queen and forms a cluster within 20-20 metres of the original hive. My bees usually land on one of the trees on the allotment. This makes collection easier than when they choose a neighbouring plot.

The bees cluster around the queen for a few days while scout bees search for a final home. Once this has been decided, the bees will head off to take permanent residence there.

Minimising the risk of swarming is an important aspect of beekeeping, especially if you keep them in urban or public areas.

The first swarm was a small one and to this day I don’t know where it came from. The second swarm was huge. These are known as primary swarms. This swarm began while I was on the plot so I saw them leaving the hive – one I’d checked two days previously and not seen any queen cells. The bees are good at hiding them. There seemed to be plenty of space so it took me by surprise but that’s beekeeping for you!

Collecting a swarm gets easier with practice. Swarm boxes are ideal for the purpose. They’re like a mini portable hive. Place it beneath the swarm. If the cluster is hanging from a tree, tap the branch and in theory the cluster will fall into the box. It works most times although there are always exceptions.

A vital part of swarm collection is a white sheet spread out below the swarm. Once the main cluster has fallen into the box it usually includes the queen who is in the centre. You then need to catch all the flying bees.

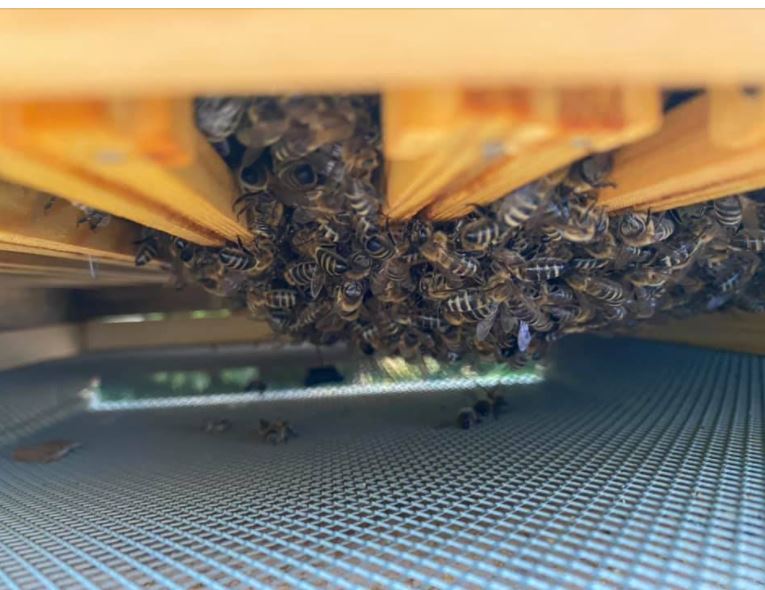

Turn the box upside down on the sheet and prop up a corner with a stone or log. The bees will smell their queen and walk in through the gap to join her. Leave till evening when the majority of bees will be in the box. Then I upright it, put on the lid, open the mesh windows and leave them overnight to settle.

Hiving a swarm is one of the best parts of beekeeping. Upend the box over a new hive. The majority of bees will fall in but there will be fliers. I like to prop up a ramp (miine is an old cupboard door) with one end at the hive entrance. Cover the ramp with your sheet and the bees will walk up the ramp and into the hive. It’s not essential to do this. The flying bees will eventually follow their queen but I like to watch them.

Some bees stick their bums in the air to release a ‘follow me’ pheromone. This guides the other bees towards the hive entrance. The video below shows the last swarm stragglers being directed towards the collection box.

Most local Beekeeping Associations have collection teams who will come out to swarms reported by the public. They only respond to honeybees so will probably ask for photographic evidence to check the swarm is not connected to a bumblebee or wasp nest. If you find a swarm it’s always worth contacting them rather than tackling them yourself. Local associations can be found here https://www.bbka.org.uk/find-beekeeping-near-you.

Some people destroy swarming clusters but this is the worst solution. Pollinators are in increasingly short supply, under threat from changes in farming such as monocropping and the use of pesticides. We need to protect our bees.

Swarms are potentially a nuisance if they choose a house or garden shed to make a new home, but swarming can be good for the bees. It gives them a ‘brood break’ which helps defeat the varroa mite which feeds on young larvae. It’s also a sign of a strong and healthy colony.

Keeping bees is never easy but it’s an incredible experience!

One thought on “Swarming bees”