Bees are known for being unpredictable. No matter how many books or videos you consult, the reality is always different. Plus – it doesn’t help that bees do neither!

Keeping bees is one long learning curve and I’ve had a hard lesson about starvation.

April began warm then changed to colder than average. A previous post, Getting stung when I should know better, covered these early weather problems and how the bee inspector cancelled a visit at the last minute because temperatures were too low.

By the time he arrived in early May, the bees were busy catching up. The inspector suggested adding a second super box for stores (which they rapidly filled with nectar) and when we saw queen cells in one colony it seemed they were thinking of swarming, so we removed the queen and set her up in a smaller hive, known as a nuc.

Despite May being declared the warmest since records began, there was a lot of rain and the bees struggled to forage.

At the end of the month, during a weekly inspection, I noticed the bees in the nuc seemed quieter than usual. There were dead bees on the wire mesh floor and a general sense of lethargy. Capped brood on the inside frames showed the queen had been laying, but several cells had pierced cappings.

As this can be a sign of disease, I did the usual checks. The larvae was pearly white and well segmented, like they should be, and my notes show I thought maybe the nuc had gotten chilled. Smaller colonies can struggle to keep warm, especially when it’s cold, so I removed the outer frames and replaced them with solid dummy boards, thinking these might help reduce heat loss.

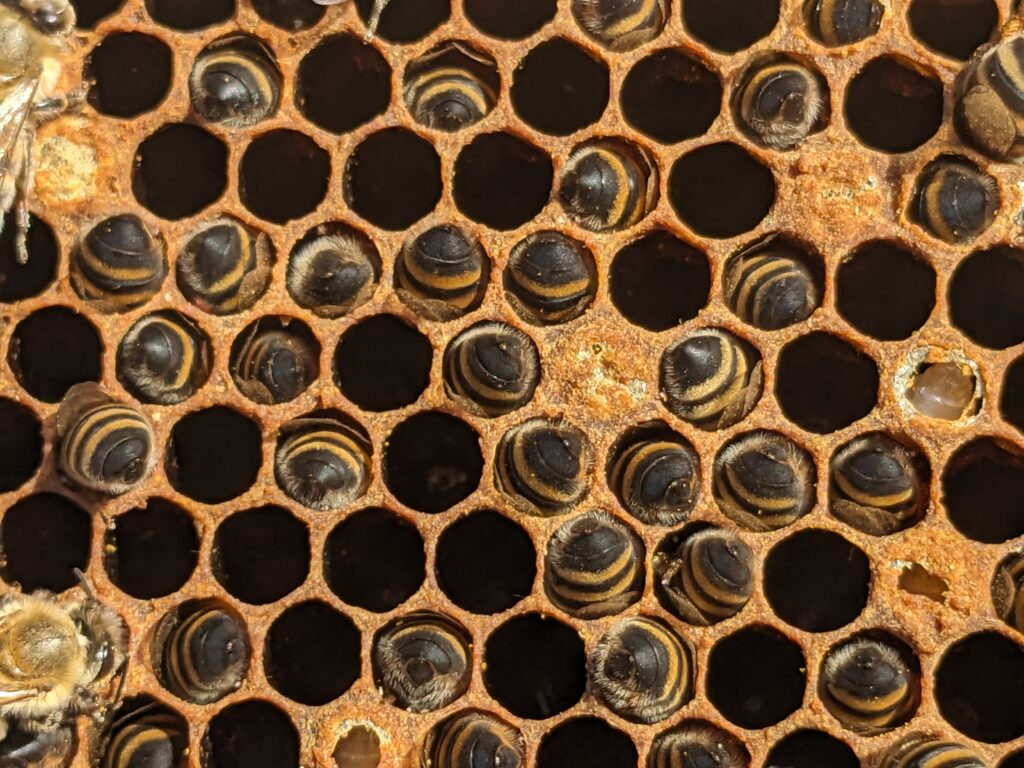

Worried about them, I went back to check the next day. This time, I saw a cluster of bees head down in the cells, almost totally inside them, and it clicked. The lethargy was a symptom of starvation. I hadn’t left enough stores and the bees were hungry. Having consumed what they had, they were now desperately seeking the last traces of nectar, while the pierced cappings were a sign of them hunting for food.

I felt terrible!

Over the past few years, I’ve made many beekeeping mistakes but this felt like the worst, especially because the queen was still alive. My starving bees were dying but still prioritising her survival.

There was fondant in the bee shed so I shaved off thin slivers and placed them on the top of the frames where the bees could get to them easily. There was also some sugar syrup, but the bees wouldn’t take it earlier in the year. I’d added cider vinegar, which is supposed to stop the syrup going black and mouldy. Maybe I’d got the proportions wrong but whatever the reason, I was reluctant to offer it. The fondant was an emergency measure only. Bees need water to process it and these clearly didn’t have strength to fly.

Feeling responsible for their distress, I left a plant pot holder full of stones and water by the nuc entrance and consulted the National Bee Unit for advice. Their list of suggestions for food included honey.

I ran to the car for a couple of jars, smeared a frame of foundation and they loved it.

The weather was iffy. Despite the warmth of an intermittent sun, I was concerned about potentially losing this weakened colony, so covered the frame tops with honey, replaced the crownboard to keep the heat in and emptied the jar on top.

They were up and out in no time.

One even found her way onto the jar itself.

The next day the honey had all gone. Determined to ‘save’ a colony which had kept their queen alive while they were starving, I took a frame of capped stores from a different hive and donated this to the nuc. Then I left them alone for a few days to recover from the intrusions and feed as much as they wanted.

Yesterday, I saw eggs and tiny larvae which suggests the colony is going to survive. Phew…

Ensuring stores throughout winter is one thing. Don’t take all their honey. Learn to lift or heft the hives in late autumn, then regularly throughout the winter months so you can judge if they’re getting lighter. This indicates the need to feed without having to look inside and chill the cluster. If they seem light on stores, feed with fondant. Sugar syrup can be used in the spring, before there is sufficent forage, and again if stores are low in autumn. They will store this for the colder months ahead.

I missed all the signs of summer starvation.

It was the beginning of June and I connected hunger with winter, not 3 weeks before the summer solstice. Now I know what ‘head down in the cells‘ looks like. I’d read about it but seeing it for real was the best lesson. Also, giving them honey as an instant source of food wasn’t the first thing I thought of.

Talk about not seeing the ****ing obvious!

While all this was going on, other colonies were swarming. Two days running. I got to see the second one from start to finish and that experience will be the next blog post.

Beekeeping – never a dull moment!