Pause for a moment – close your eyes – think of the word witch.

What do you see?

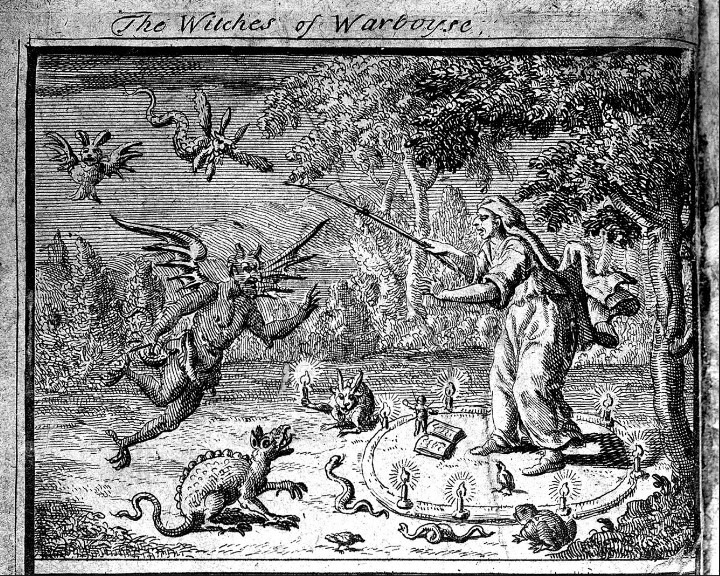

Even without the giveaway of the image above, chances are high there’ll be a hat, cat, cauldron, broomstick… maybe a devil or two but always the colour black, and the face and body of an older woman.

The word witch has been successfully appropriated. I don’t think there’s another word where fact and fantasy are so interwoven we can’t tell them apart. Reinforced through centuries of stories, through art and literature, historical records and religion, the negative connotations of a witch remain with us today.

Look at this entry from my thesaurus, published in 2019.

Society is still pushing the stereotype.

There’s the witch and there’s witchcraft; a social identity and a cultural practice. This post looks at the witch while what witches do will be a separate post.

You may be familiar with some of these:

- Lilith, the first wife of Adam, known as sorceress, demon and witch.

- Hecate, ancient triple goddess of the night, dogs, crossroads and witches.

- Circe, offered shelter to Odysseus, turned his sailors to pigs and gave him a spell to enter the underworld.

- Witch of Endor, visited by King Saul, she summoned the spirit of dead Jewish prophet Samuel.

- Morgan le Fay, half sister to King Arthur of 5th century Britain and connected to the Isle of Avalon.

Myths and legends are full of witches but historical records also support the belief that women could cause and control change.

Other names from the witch trials which may be familiar include the Pendle or Lancashire Witches, the North Berwick Witches, the witches from St Osyth in Essex and from Warboys in East Anglia. Future posts will explore the background to these and more, including the Salem witch trials in 17th century Massachusetts.

The word witch has been with us for millenia. There have always been women, othered by difference, who became scapegoats for a community’s dissatisfaction and fear. Countless numbers faced accusations of witchcraft, and went to their deaths both innocent and nameless.

Let’s talk about witches.

We know they were predominantly female, alleged to have the power to harm or heal.

Often – but not always – in their crone years and marked out through physical features, they might be missing a part of their body, have damaged limbs or faces, and be visually different.

Often – but not always – impoverished and already living on the edges of a community, they had medical knowledge of plants. Known for midwifery skills or the ability to set broken bones, they were the go-to person for charms and spells for love or revenge.

Already with a reputation for magic or sorcery, these women became scapegoats when damage happened to livestock or harvests, or when someone fell ill or became victim of an accident without obvious cause.

Medicine can seem magical. Many of todays pharmaceuticals have their origins in plants and it’s worth bearing in the mind the third law of science fiction writer Arthur C Clarke who suggested any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

The word magic itself has ancient roots. Used as an explanation when existing knowledge failed to provide answers, it’s been associated with prophecy, divination, and necromancy in many ancient civilisations, but it was the development of Abrahamic belief systems where witches and witchcraft became irrevokably associated with evil.

Before moving onto the influence of religion we need to place superstition alongside magic because they both share belief in the supernatural. Anything unexplained by natural laws i.e. supra naturam – above or beyond the natural – can be labelled superstitious. In today’s world of science, old superstitions remain alive in beliefs such as black cats, Friday 13th and spilt salt being unlucky.

Many communities developed their own work related superstitions such as those believed to protect trawler men in the fishing industry. They’re useful examples of actions unsupported by facts, which nevertheless give comfort or reassurance.

If you believe in a superstition you’re demonstrating a position not so different to the villagers who believed the devil and his demons were responsible for milk going sour or cows developing the pox – and where there’s devils there’s witches.

The church has played a major role in our conception of the witch. Already supporting mysogynistic attitudes, war was officially declared on heresy in the 12th century, and the Inquisition established to persecute anyone not following its beliefs. Witchcraft was a prime candidate.

A book published in 1486 by Heinreich Kramer, the Malleus Maleficarum or Witches Hammer, went into great detail about how to identify a witch, alongside the torture techniques required to elicit confessions. It remains a horrifying read and a separate post will examine this book more detail. Some of it would almost be funny, such as the witch and the penis tree, if it weren’t for the fact that men in power believed it to be true.

By the 16th century, the Inquisition was the leading proponent of the persecution of women as witches.

17th century England was also influenced by King James 1. With a morbid fear of witchcraft he authored Daemonologie, a book thought to have influenced Shakespeare’s portrayal of the three witches in Macbeth. James also oversaw a new translation of the bible, the King James Version, which included the line Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live (Exodus 22:18) where he had the word previousy translated as sorceror or poisoner changed to witch.

Court records from this time share similar details.

A woman was approached by the devil who promised power in return for sex. Once she had agreed and signed a pact, usually in blood, the devil would order his demons or imps to carry out her demands to cause harm to those who had wronged her.

The demons would take the form of a dog or other small animal, known as a familiar, and there would be a place on her body called a witches mark, where it suckled. Witches would gather to dance in celebration of their relationship with the devil. These sabats often included the Osculum infame or devil’s kiss and they would be scenes of much debauched behaviour.

Once accused and found guilty of witchcraft, the women were sentenced. In 1542 Parliament had passed the Witchcraft Act which defined witchcraft as a crime punishable by death. James 1 passed another law in 1603 which extended the number of witchcraft crimes, all of which carried the death penalty. Although witches were persecuted for hundreds of years, the 17th century was the worst of times. We do not know how many women died as witches but the majority were poor, illiterate and effectively helpless.

By the 18th century times had changes. The Witchcraft Act of 1735 made it a crime to claim anyone had magical powers or practised witchcraft. This effectively dismissed the idea that magical power existed. If you claimed to practice magic you were a liar and if you exchanged alleged magical power for money, you were a cheat. Yet belief in witches continued. The stereotype has deep roots.

The 20th century saw a resurgence of interest. Witchcraft was relabelled as wicca and witches became wiccans. The internet currently supports thousands of modern witches sharing their lives, spells and practices. Times have changed but the identity of witch remains constant which opens up a range of related topics to be dealt with in future posts.

2 thoughts on “Let’s talk witches”